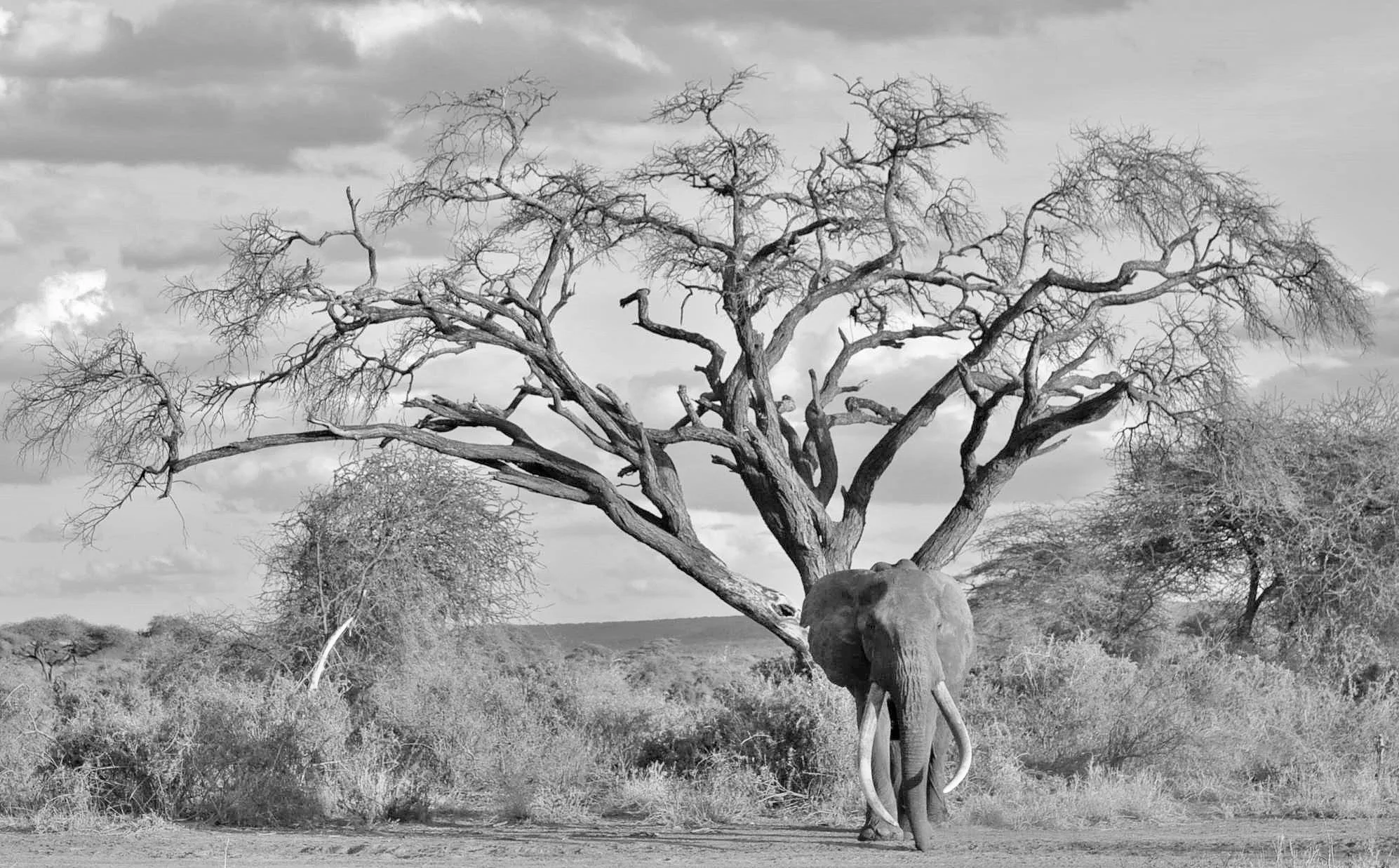

Saying goodbye to the giant, Craig - writes Zarek Cockar

photo credit: Zarek Cockar

Craig, one of Amboseli’s last great super-tuskers, died in January of natural causes. In a time when elephants with tusks of his scale are increasingly rare, the fact that Craig lived to old age matters. Not because he was famous, but because his life quietly demonstrated what long-term, consistent conservation can achieve when wildlife is allowed to grow and age is they should.

Craig spent decades moving through the Amboseli ecosystem much as elephants have for generations - eating, migrating, competing and aging within a protected landscape. He survived periods of intense poaching pressure across East Africa, changing land use around the park and changing management systems, along with the constant presence of an ever growing population. Yet he was not removed, relocated, or managed excessively.

Conservation success is often framed in moments of crisis or rescue, but Craig’s life reminds us that success can also look quiet and slow. It can look like an old bull growing slower each year, wearing his tusks down through use rather than losing them to human greed. It can look like an animal dying not because he was targeted, but because time eventually catches up with even the strongest.

For those of us living and working closely with landscapes, wildlife and communities, Craig’s passing is not just the loss of an individual elephant, but instead proof that protection, when rooted in local stewardship, enforcement and patience, can still create space for wild animals to live full, uninterrupted lives.

As a guide, I believe conservation is about continuity - ensuring that wildlife has the time and space to exist as wildlife, and that the people who share these landscapes are part of that process. It is this story that I share with my guests, as I lead them through Kenya and beyond, whether it is their first or 100th time in Africa.